Breaking and Creating: How Autumn Leaves Unite People

Jade Tsang

Jade is a graduate landscape architect based in our London studio. She is passionate about bringing nature and urban spaces together; promoting ecological connectivity and supporting the resilience of local ecosystems.

秋の夜を

打ち崩したる

咄かな

<English>

In the autumn night,

Breaking into

A pleasant chat.

Autumn air in Japan carries a crisp and refreshing scent, a stark contrast to the humid summer, signalling the onset of the barren winter. Leaves go through cycles of life and decay, like people gather and disperse. For the renowned Japanese poet, Matsuo Bashō, autumn nights symbolise a time of ‘breaking and creating’. People gather to admire the magnificent but fleeting autumn leaves, symbolising ‘breaking’. Then, they break the ice and engage in cheerful conversations, representing ‘creating’. Nature has provided essential materials for landscape design. By merging emotions with the environment and aligning with seasonal changes, we can foster spaces that encourage vibrant interactions.

The spectacular display of autumn leaves is a result of annual solar variations. During the sun-filled spring and summer, chlorophyll in the leaves converts sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water into nutrients. As daylight shortens in autumn and winter, deciduous trees stop producing chlorophyll, leaving behind pigments that reflect the sunlight’s damage. This natural process celebrates the cycle of life and death, turning leaves into beacons of sunlight. The scene of red foliage covering mountains captivates many peoples’ hearts and has become a unique cultural symbol in Japan. In Japanese culture, the autumn foliage is not only pleasing to the eye, but it also serves as a poignant ‘memento mori’, reminding people of what is important in life through the temporary brilliance of plants… ‘Let’s watch the red leaves together at some point’, becomes a reason for people to gather.

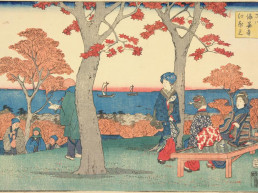

This unique annual spectacle has given rise to ‘Momijigari’ (red leaf hunting) in Japan. ‘-gari’ was initially defined as hunting animals, later extended to seeking autumn leaves, with maple and ginkgo trees attracting the most attention. However, there is no need to go far and see, since these trees are ubiquitous. Vivid autumn foliage has high aesthetic value, making them popular in parks, temples, shrines, and even city streets. Momijigari is a significant cultural tradition in Japan, a social activity, and a source of artistic inspiration.

Momijigari originated during the late 8th century Heian period, as an elegant social activity. Aristocrats would visit forests and gardens in autumn to hold banquets, admire the leaves, and compose poetry, blending nature appreciation with cultural arts. Later, samurai combined contemplation of autumn leaves with Zen meditation, reflecting on life’s impermanence in forests or temples to strengthen mental discipline and enhance their martial arts skills. By the 17th century Edo period, Momijigari became a nationwide activity, incorporating photography, hiking, and gatherings, becoming an indispensable part of autumn.

The enthusiasm for autumn leaves is not confined to Japan. In the United States and Canada, a similar activity known as “leaf peeping” thrives. In these car-dependent nations, road trips are popular, especially during peak foliage season. Scenic parkways, farmers markets, and harvest events stimulate local economies in regions famous for their autumn leaves. While Momijigari in Japan is rooted in a rich historical and cultural context, leaf peeping in North America is more driven by media marketing and tourism economics. Despite regional differences, the universal appeal of autumn leaves may be linked to evolutionary processes. Our fondness for vibrant autumn colours possibly stems from associating them with ripe fruits or harvest seasons, which evoke warmth and satisfaction.

In the UK, autumn transforms London’s surrounding Royal Parks, such as Richmond Park and Kensington Gardens, into landscapes of classical beauty with vibrant foliage. The southwest of England is known for its rolling countryside and forests, and locations such as Exmoor National Park and Montacute House are ideal destinations for viewing autumn leaves. When designing planting schemes in the UK, it is essential to balance evergreen and deciduous plants, often embellishing with seasonally distinctive species, especially those with striking autumn leaves. Native British deciduous trees like oak, field maple, and beech also offer spectacular autumn colours in red, orange, and yellow hues, making the natural seasonal changes palpable in both rural and urban settings.

Could Britain’s autumn culture become as mainstream as Japan’s Momijigari or North America’s leaf peeping? The possibility exists. Perhaps extended from discussions on the “freedom to roam” in the past, walking and hiking are deeply ingrained in British tradition. Combining these habits with autumn leaf appreciation might create a unique autumn landscape culture in the UK. Whether through top-down promotion by government bodies of specific hiking routes, or bottom-up initiatives organising autumn leaf-themed festivals in national parks and rural areas, the beauty of autumn leaves can become part of every Brit’s autumn memory and unite people.