Steps towards a Sustainable Future

Blogs

Lucy Edwards

Lucy is an Architect at BoonBrown with a passion for sustainable, context driven design that responds sensitively to the needs of both users and the environment. As a member of BoonBrown’s Social Value Committee, Lucy is championing carbon footprint awareness and environmental initiatives within the office.

Our Commitment

As part of BoonBrown’s Social Value Strategy, over the last two years we have been calculating and tracking the Carbon Footprint of our Southwest and London Studios.

As a practice, we are committed to reducing our carbon footprint to achieve Net Zero by 2040. This aligns with the government’s goal to achieve Net Zero emissions in the UK by 2050. The first step in reducing our carbon footprint is to measure our existing impact so that we can identify areas of improvement to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. For emissions which cannot practicably be reduced, we will look at offsetting measures to reach our target goal of Net Zero.

This initial exercise of measuring our existing carbon footprint has highlighted some interesting findings and statistics, helping to raise awareness of our environmental impact, both collectively as a business and individually through our own day-to-day habits. We are now well placed to identify steps we can take to actively reduce our emissions and have a better understanding of the remaining emissions which will require offsetting.

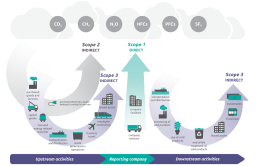

Scope 1, 2 & 3 Emissions

There are three ‘Scopes’ which make up our Carbon Footprint calculations, as defined by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol) established in 1998:

- Scope 1 covers all direct emissions from sources controlled by an organisation, such as burning fuel in company vehicles, refrigerants, and burning gas in boilers.

- Scope 2 includes indirect greenhouse gas emissions from purchased energy, such as electricity, heating, cooling, and steam.

- Scope 3 covers all remaining indirect greenhouse gas emissions from activities, from sources not owned or controlled by an organisation.

Scope 1 and 2 emissions are generally easy to quantify and record. However, Scope 3 emissions are much harder to measure despite typically accounting for 65% – 95% of an organisation’s total Carbon Footprint. Measuring Scope 3 emissions requires extensive assessment of the supply chain, including both upstream and downstream activities, and often relies heavily on estimates and third-party data.

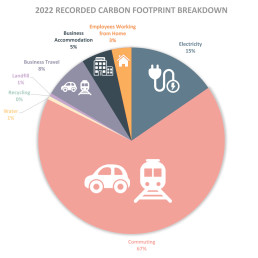

BoonBrown Carbon Footprint

Our Carbon Footprint is calculated in tonnes of CO2e, or Carbon Dioxide Equivalent. This is a metric measure used to compare emissions of different greenhouse gases based on their global warming potential. For example, emitting 1kg of methane has the same global warming potential as emitting 28kg of carbon dioxide, and is therefore equal to 28kg of CO2e.

At BoonBrown, our Scope 3 emissions account for approximately 85% of our total Carbon Footprint and are broken down into the following categories:

- Employee Commuting

Calculated based on miles travelled, by transport and fuel type.

- Business Travel

Calculated in the same way as Employee Commuting.

- Business Accommodation

Based on number of nights spent in hotel accommodation.

- Waste and Recycling

Calculated based on total weight of items recycled or sent to landfill, which is recorded as part of our ISO14001 processes.

- Water Usage

Calculated using total water consumption in m3.

- Employees Working from Home

Based on average number of days per week spent working from home.

We used the Small Business Carbon Calculator created by Climate Impact Partners to convert our collected data into tonnes of CO2e.

Our total Carbon Footprint for 2022 was calculated at 80.11 tonnes CO2e, equal to approximately 20 elephants! A full breakdown of our calculations and the emissions attributable to each of the above categories is available in our Carbon Reduction Plan on our website here.

What have we learnt?

This exercise has been an enlightening process and allowed us to learn more about the theory behind carbon footprint calculation and better understand the environmental impact of our practices and individual actions. Sharing the findings with our teams in London and Yeovil has given weight to the environmental procedures we implement as part of our ISO14001 accreditation, encouraging staff to adopt new ways of working to reduce our carbon footprint.

As expected, our Scope 3 emissions account for most of our carbon footprint. However, we were surprised to learn that emissions from employee commuting make up such a large portion of this. This is partly down to several members of the southwest team commuting substantial distances to the office every day – journeys that would be difficult to undertake on public transport or by bike! This is an obvious area where we could make an improvement, and we intend to further explore options for reducing this impact next year.

Likewise, there are areas for improvement in our carbon footprint calculations. Since 2022 is the first full calendar year in our new London studio, much of the data for London has been calculated based on averages in the southwest office. Over 2023, we have increased our data collection in both studios which should improve the accuracy of our calculations. We also plan to include emissions from our purchased goods and services to give a fuller picture of our total carbon footprint.

Carbon Reduction Initiatives

Our Carbon Reduction Plan outlines both our implemented and proposed carbon reduction initiatives in detail. Below are some examples of initiatives at an individual level that all employees are implementing in their day-to-day working practices:

- Encouraged staff to switch to ‘green’ search engines, such as Ecosia, which uses profits from advertising to plant trees across the globe.

- Removed individual desk bins, to encourage proper recycling of waste.

- Turning off equipment when not in use, including lights, printers, PCs overnight and monitors when not at your desk.

- Only printing when necessary.

- Encouraged car sharing when commuting or attending remote meetings.

- Unplugging electrical items when fully charged and switching to reusable batteries where possible.

As a practice working in the construction industry, we are well placed to make positive ‘greener’ choices when designing and delivering our projects, encouraging and assisting clients to incorporate sustainable technologies and reducing the carbon impact of development where possible. As we develop our Net Zero strategy, we plan to actively seek opportunities for further offsetting solutions such as tree planting and habitat creation.

As the first full calendar year in our new London studio, 2022 will form our baseline Carbon Footprint calculation for both BoonBrown offices and we aim to see reductions in our collective Carbon Footprint year-on-year. When looking at the Yeovil studio alone, we have seen an estimated 12% reduction in our Carbon Footprint from 2019 to 2022 and we hope to see this positive trend continue over the coming years.

New pathway to becoming an architect

Blogs

Written by

Sydney Wheeler

Sydney is currently studying at the University of the West of England in Bristol and is in her 2nd year of the Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship.

Martin Bignell

Martin is currently studying at the University of the West of England in Bristol and is in his 2nd year of the Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship.

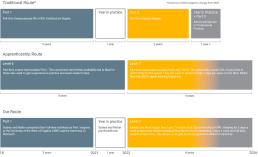

For many, embarking on the route to becoming an Architect seems like a lifetime. The traditional 7-year minimum path now includes an apprenticeship option, offering academic knowledge and practical application whilst earning a salary. Although this pathway is still a relatively new route to qualifying, it is becoming more and more popular within universities and architectural practices.

After completing our Part 1 placement year, it was apparent that the knowledge and skills you learn whilst being part of a practice surrounded by professionals is invaluable. The mentorship and guidance that we received within the year out exposed us to challenges and complexities in the industry allowing us to enhance our understanding of how theoretical knowledge translates into real-world applications. We were able to develop essential technical skills in areas such as design, software, construction techniques, project management and building regulations to gain a hands-on experience and a greater opportunity to embrace innovation for the betterment of the built environment.

When considering our next steps to qualify, we had to evaluate the options of studying full-time, part-time or on the new Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship. The benefits of the apprenticeship route allowed for a more accessible and inclusive educational pathway, whilst still being accredited by professional bodies. Studying for 2 days a week, during term time, with the remainder of the year working full-time, we will be able to complete our Part II and Part III in 4 years. Although the timeframe doesn’t differ massively from studying full-time, completing a Part II placement year and finishing your Part III, it has the additional benefit of it being all included within 1 programme. Many people defer their Part III as they are tiresome of academia and become comfortable in their practice. However, the apprenticeship will keep us focused and ensure that we do not prolong the already extensive pathway.

95% of apprenticeship tuition fees are paid by the government with the remaining 5% paid by your workplace practice therefore no student loan is required.

Sydney’s Personal Experience:

‘When considering the routes to qualification as an Architect, I knew that returning to university full-time was not an option. Throughout my undergraduate degree, I had countless bad experiences living in halls accommodation, coronavirus and family emergencies where I was unable to get home. Living away from home, with the long commute, proved to be a real struggle and resulted in my mental health deteriorating. The apprenticeship route has allowed me to stay close to home, whilst earning a full-time salary, and continue my studies to becoming fully qualified. As a result, I have been able to maintain flexibility and financial independence which has allowed me to successfully buy my first home and embark on growing my family by getting a dog.’

As an apprentice, there are government standards that you must fulfil which include having a specific workplace mentor. This has allowed us to gain comprehensive training and support to ensure that our development covers all the RIBA work stages whilst offering valuable feedback and supporting us on our journey. Alongside having a workplace mentor, working closely with other experienced individuals in the office allows us to grow, both personally and professionally, to become more competent and confident. The government apprenticeship requirements also require us to log ‘Off the Job Hours’. These are hours that we have spent learning something new or developing a knowledge, skill or behaviour such as our university lectures, shadowing meetings or reading a relevant book. By recording these hours, it allows us to fully understand the standard that is required of us to be fully qualified and gives us a clear path towards the final gateway. With help from our workplace mentor, we can ensure that we record our development against the criteria to gain experience in all areas of architecture.

Despite all the benefits of the apprenticeship, the work ethic is incredibly demanding and is by no means easy or easier. Having to complete all of our university work, our ‘Off the Job Hours’ and PEDR’s, alongside general living and working full-time is definitely a struggle. With just the evenings and weekends, we have had to make many sacrifices to try and complete the work however this is something that we have not yet mastered.

The combination of working and studying pushes our time management to the limits where at university we are still expected to produce work within the same timescales and standard as a full-time student, without the additional time and days. This aspect of the course was something that we were totally unprepared for. Although we knew the workloads would be heavy from our undergraduate degree, the aspect of an apprenticeship made us think that the submissions would be altered due to us working full-time with the exception of timetabled university days, however this is not the case.

Martin’s Personal Experience:

‘Undertaking the apprenticeship means that you miss out on the typical ‘university experience’ as you have limited exposure to the university setting. However, this is not much of a sacrifice as I have already had this experience from my Part I degree at the University of Plymouth and feel as though the benefits of the apprenticeship outweigh the reduction in social opportunities.

Studying part time at university allows me to research and design using innovative and exciting advancements, whilst working in practice increases my knowledge on current technologies and regulations. Developing my knowledge and attitude towards learning will help me prepare for my future in Architecture.’

After experiencing our first year of the apprenticeship, we often ask ourselves if this is something we would do again and whether we made the right choice. If there were no variables to consider, and it was between full-time education and the apprenticeship, full-time would be preferred as the educational pathway allows you time and space to fully delve and explore the creative briefs. However, taking into consideration all of the above benefits including a full-time salary, being close to home and family, no student loan and the amount of valuable work experience, the apprenticeship is definitely a great choice as it offers a well-rounded and practical approach to learning and qualification, preparing us for a fulfilling career in architecture.

Routes to Qualification

All under one roof: a home for generations

Blogs

Great news – we have secured planning permission for one of our biggest home transformations yet…!

Our project at Thorpe Avenue in Peterborough extends the existing 240sqm dwelling to 610sqm, providing three reception rooms, an open kitchen/living/diner, swimming pool, nine bedrooms and ten bathrooms.

The house is soon to become home to a large multi-generational family – with construction due to the start later this year.

The Brief

The brief for this project was fascinating. One of the main objectives was to deliver a significantly increased floor area to cater for the large family, but also to include bedrooms of consistent sizes, to ensure family members have access to comparable spaces and facilities. To provide this increase, the design needed to be carefully balanced against impact upon the existing home, which itself had its own unique character.

To deliver a successful architectural proposition, we established four main design principles:

- The design must not overbear and detract from the character of the existing dwellinghouse and adjacent properties. The extension must be sympathetic to the Local Authority’s Special Character Area, with special emphasis placed on retaining the area’s landscape and architectural style.

- The proposal should be reflective of its constructed era, as per the surrounding buildings which are the style of their period.

- The large floor area requirement must not be to the detriment of space and light quality within the dwelling.

- The design must relate to the street settlement pattern, turning the corner between Thorpe Avenue and Thorpe Road.

The Design

Massing was an important factor in achieving these principles. The design includes several small infill extensions that maintain the style of the existing house, however its main wing extension to the south is broken into two architectural elements, in a more contrasting architectural style. The natural contour of the site presented an opportunity to step the extension down into two lower levels, which enabled the ridge and eave lines of the new extension to sit subservient to the existing house.

A series of massing studies were carried out considering the positioning of existing TPO trees, local settlement pattern and street composition, testing options for spatial arrangements. We were mindful of not adding large elements to the existing house, to avoid creating deep plan rooms that would suffer from a lack of natural daylight or view. The result takes the form of a two-storey L-shaped extension.

Examination of the local architectural context demonstrates how each house reflects the era that it was built, providing an opportunity to develop a contemporary design approach, rather than pastiche proposal. Local materials such as white render and brown brick contrast against metal detailing used as a tertiary material for louvres and gable framing. Vertical fins are incorporated across the front entrance wing with multiple practical functions; to visually break the link’s horizontal form, to provide screening and privacy for first floor bedrooms, to offer shade from morning sun and create an opportunity for plants to climb up the building around the main entrance.

Although the house has ample garden, the extension is formed around a new internal courtyard, which provides a different outside environment. This space is accessed from all sides of the home, at their respective levels, providing space for outside cooking, seating and socialising. This space is critical as it provides natural daylight and aspect from many of the rooms, also creating a central social space within the home.

Buckle up for Buckeroo or Preparing for Complexity?

Blogs

Ed Watson

Ed is a Place Specialist, focused on regeneration, place-shaping and providing strategic expertise to councils and businesses to ensure the delivery of high quality places that are economically and socially vibrant, whilst minimising impact on the environment.

The world of development, planning and architecture never stands still. Often it feels like we are struggling to keep pace with what is needed to get the basics done, let alone to make truly successful places. It’s also a challenge to get to grips with the ever-increasing levels of complexity that need to be navigated to get a scheme over the line; initially to secure planning permission and then if you are lucky, to get it built.

I call this constant change and increasing complexity the ‘planning Buckeroo’ (it could equally be referring to architecture (or policing, or health)) . For those too young to remember, Buckeroo was a 1970’s children’s game where the players took turns to load a small plastic donkey with all sorts of tools until it couldn’t take any more and ‘bucked’ the whole lot off. Needless to say that the last player to add a tool before it bucked lost the game.

I’m lucky enough to have worked in planning and development in local government for nearly 30 years and then to have spent the last five years advising a range of public and private sector organisations including BoonBrown. During this time I have seen ever more things loaded onto the planning donkey, and so it is no surprise that its legs are starting to wobble.

Given this complexity it is more important than ever to understand the challenges and motivations of our colleagues in other professions. I hope that current planning, engineering, and architecture courses pay more attention to understanding and working effectively with other professions than mine did. Shout out to the excellent @New London Architecture and @Future of London/Manchester who do great work to bridge this gap, alongside two wheeled versions such as @club Peloton and others.

So, what sort of complexity and change is coming down the track in relation to architecture and planning? Setting aside the macro impacts of the cost-of-living crisis and the failure of the post-Brexit economic phoenix to rise from the ashes, there are a few suggestions below:

Firstly, the Government is still searching for the precise combination to unlock the future shape of the planning system. How to allow the right things – let’s call it well designed and supported places – to happen in the right locations, but quicker. All while ensuring communities have a genuine opportunity to have their say and benefit from the outcome.

But do we need this change at all? Some might look at places like Kings Cross and say with the right teams and attitudes on both sides it clearly works. However, there are many places where the opportunity for good decisions and outcomes is missed. For my money I would suggest leaving the system as it is and resourcing it properly – particularly local Government. Also more talking up the great work of our planners and architects. Less trash talking please.

Can we take a few tools off the donkey? Probably not, but perhaps they can be made lighter and easier to use? In the next year the dials of the Government machine should whirr and click into place and the answer emerge. Or depending on how radical the answers are, they may not. See the next point.

Secondly, there will be a new Government in the next 18 months. If the predictions of commentators (and some Conservative MP’s it would seem as they are not standing again) are to be believed, then this will not be another Conservative Government. However, whoever is in power we should be prepared for more change – perhaps more radical and speedier if it’s Labour? Hopefully they will want to make big decisions early, having learnt from their failure to be more radical when first elected in 1997? If so, what would be the implications of Labour’s recent announcement on securing land for housing at prices more akin to their pre-planning permission/allocation value? What about ‘sensible’* release of the green belt?

Thirdly, some of the current headaches will start to clear – perhaps leading to other complexity – but at least removing the waste of time and energy that it currently takes to work in a world of uncertainty. See Tom’s last blog about 2nd stairs; but also where things are going with nutrient neutrality; national policy support for life sciences; or funding infrastructure etc.

Fourthly, the increased focus on social value will continue. Particularly how all players in the ‘development system’ can do more to address net zero, support people into work, invest in local communities and so on. It is exciting, and a bit sad because it has taken so long, to see how quickly things have started to move since companies have been required to report on their ESG performance. This requirement now extends to 1,300 of our biggest businesses. It has started to cascade through the supply chain and that is a good thing. Expect and demand more.

Finally, and this is more of a wish based on being a parent whose children need somewhere to live rather than a prediction. It is also nothing new. When, oh when, will we really try, really hard, to access the views of those who are currently excluded from the system and whose voices are not heard when deciding planning applications. How can we give weight in decisions to those who would benefit from a proposal? Perhaps we can take a punt and say that for every objection there are ten people on a housing waiting list who would support it? Too often politicians and planning committees are swayed by the vocal few who are ‘in the room’ and who think they have something to lose and little to gain from a new housing scheme in their area. I know this is not the case everywhere, and I applaud brave politicians and good officers up and down the country, but I know it happens in lots of places. Young people and those on low incomes need homes. Pre-loved or new doesn’t matter, but its existence and affordability does. This doesn’t take legislation, just willing decision makers.

So, be prepared for more change and if you can, take a walk in some else’s shoes – perhaps a planner, an architect or a young person. You might find that you learn something from the discomfort.

Reflections from Chelsea

Blogs

Moving towards a more sustainable way of planting, reflections from Chelsea.

One of the key themes from the Chelsea Flower show this year was the use of different substrates as a means for planting the show gardens. With peat-free planting mediums becoming more and more prevalent and sought-after in the landscape industry, it was interesting to see the different options on show and how these performed in the eyes of the Chelsea judges. Showing how these substrates can perform at the very highest level expands the options available for use in the landscape profession and for those at home and helps reduce the impact the planting industry has on the environment. Some key benefits to using this kind of substrate are:

- Improved drainage: Rubble and free-draining substrate allow excess water to quickly drain away from plant roots. This helps prevent waterlogging and reduces the risk of root rot or other water-related issues. Good drainage promotes healthier root growth and reduces the likelihood of plant diseases.

- Enhanced aeration: The presence of rubble and free-draining substrate allows for better airflow to plant roots. Oxygen is vital for root respiration and overall plant health. Improved aeration facilitates nutrient uptake and supports the growth and development of plants.

- Reduced soil compaction: In urban areas or places with compacted soil, rubble and free-draining substrate can help alleviate soil compaction. Compacted soil limits root growth and reduces the movement of air and water within the soil. Planting in rubble creates air pockets and open spaces, promoting root penetration and healthier root systems.

- Utilization of urban spaces: Planting in rubble and free-draining substrate enables the use of spaces that would otherwise be unsuitable for traditional planting methods. Urban areas often lack adequate soil for planting, but rubble and free-draining substrates can create viable growing environments in spaces such as vacant lots, rooftops, or urban gardens.

- Erosion control: Rubble and free-draining substrate can be used to stabilize slopes or areas prone to erosion. The materials can help retain soil and prevent the loss of topsoil during heavy rains or wind. By establishing vegetation in these areas, plants with deep root systems can anchor the soil, minimizing erosion risks.

- Aesthetically pleasing landscapes: When appropriately designed and maintained, rubble-based planting systems can create visually appealing landscapes. By integrating plants into urban environments, these methods can soften the appearance of concrete and other artificial elements, improving the overall aesthetics and creating a more pleasant environment for residents and visitors.

- Biodiversity promotion: Planting in rubble and free-draining substrate can contribute to urban biodiversity. These unconventional planting methods can support the growth of a wide range of plant species, including those that are well-adapted to arid or challenging conditions. By increasing plant diversity, it can attract pollinators, birds, and other wildlife, enhancing the overall ecological value of the area.

- Weed-control: The use of sterile mulches have in recent years been promoted by the likes of Nigel Dunnett. Such sterile mulches as gravel and weed-free green compost provide a non-chemical approach to establishing planting with minimum competition from weeds. It helps to establish the plants within a clean environment, plants are able to get their roots down into the soil beneath, but weed seeds or vegetative fragments in the underlying soil will be prevented from pushing up through the mulch.

- Seasonal benefits: Planting directly into sand protects roots and plants in the winter, whilst also helping to reduce moisture leaving the soil in the intense heat of the summer, acting as a mulch.

It’s worth noting that the success of planting in rubble and free-draining substrate depends on factors such as plant selection, appropriate watering, nutrient management, and ongoing maintenance. Additionally, site-specific conditions and local regulations should be considered when implementing such planting methods.

Doubling Up: Tall buildings and two stairs

Blogs

Treading carefully – is the mandating of second staircases in new tall buildings on the horizon?

As part of an ongoing update to elements of Approved Document B, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities has completed a period of consultation, with the expected conclusions to recommend mandating second staircases in new residential buildings over 30 metres tall.

Such a ‘step change’ in the approach to designing tall buildings will have a significant impact on the plan and layouts, with the stair footprint and interactions requiring accommodating and variation from the established approach; with a single, central stair.

It will affect the internal Net to Gross ratio’s that determine a projects’ viability, including accounting for the area at ground floor, along with the additional emergency egress points to engage with the site and its context. There will likely be implications for the façade treatment and loss of high value perimeter, with potential further effect on other functions within the building, such as services runs, ancillary areas, etc.

Depending on the design, there are times when a second stair can be introduced within the existing stair volume, as an interlocking, or scissor stair. Unfortunately, while this increases escape capacity when appropriate, it is ruled out as a residential solution due to the open void and the need to ensure that the building is easily navigable by both the fire service and residents i.e. at least one staircase must be kept clear of smoke, if the other is overwhelmed.

The implications of the new regulations will require design teams to seek guidance from fire consultants earlier in the project programme, during the initial project work stages, to ensure that layouts are compliant.

Whilst not yet confirmed, it is highly anticipated that any transition period within the building regulations will be very short. Therefore, factoring in a second staircase at the very earliest stages of a project is important to limit the potential impacts on viability, site constraints, specifications and aesthetics.

In fact, since February, the Greater London Authority (GLA) is no longer accepting planning applications for residential towers over 30m, which rely on a single staircase means of escape, irrespective of Building Regulations requirements. The inference is that all new residential towers over 30m should be designed to accommodate two independent stair cores. However, without clear regulatory guidance, compliance is left to interpretation.

Unsurprisingly, we are seeing this hold up developments in London where sites are tight and two stairs are not spatially possible (without compromising viability at least). In anticipation of these changes, some clients with recently approved schemes with a single stair core, are looking to redesign layouts to incorporate a second –concerned that it may not be able to deliver the current scheme.

This move by the GLA reflects the general heightened awareness and concern for safety, for obvious reasons and by acting now, lives may be saved in future, so who can blame them? However, the GLA in acting unilaterally and in advance of the expected revisions to Building Regulations, has also left designers and developers in a quandary. They have also not taken the London Fire Brigade’s advice to implement the two-stair strategy in buildings over 18m – instead making the distinction at 30m.

Space planning and rationalisation of layouts is a key element of design development and at BoonBrown we already adopt a policy of reviewing layouts for optimisation, from the concept design stage, as part of our internal technical audit procedures.

In addition, as required by the ‘Gateways’ for high rise residential developments, introduced in 2021, the inclusion and interaction with specialist fire consultants during the feasibility, concept and planning stages of tall building is ever more important.

As a practice, with studios in London & the South West, we are already taking action in line with the above requirements, regardless of the likely formal rule changes. We will be reviewing all of our tall projects to ensure a robust and viable future.

Mandatory changes to the planning process: Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG)

Blogs

As of November 2023 (TBC), it will be mandatory for developments requiring planning permission to achieve Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG). The Environment Act 2021 introduced the requirement that new planning applications for development meet the following objective ‘biodiversity value attributable to the development exceed the pre-development biodiversity value of the on-site habitat by at least 10%’.

Land development is one of a number of factors that has contributed to the degradation of the natural environment, by providing a more meaningful and quantifiable approach to biodiversity value – the environment can be enhanced by development and land/estate management through the principles and process of Biodiversity Net Gain.

At BoonBrown, our Landscape Architects work closely with Ecologists to realise the biodiversity requirements of a site. It is imperative in this process, that Landscape Architects and Ecologists are brought on board early on in a design project to seek to maximise the biodiversity value of a site, whilst also leading to enhanced places to work and live – effectively creating places and spaces of benefit to all – centred around nature. We balance site-specific requirements against other environmental concerns, such as flood mitigation and the need for landscapes to be resilient to climate change. We are also experienced in producing Landscape and Ecological Management Plans and working alongside Ecologists to deliver Biodiversity Enhancement Management Plans – to maximise the benefits of your site.

As part of the requirements of BNG, it is essential that solutions are designed and built to last and to achieve the required distinctiveness and condition as intended – in line with the minimum maintenance period of 30 years, we are able to produce dynamic landscape and ecological management plans that can be adapted throughout this period – to ensure that the habitats and spaces created are fulfilling their potential and are designed for the long-term. It is critical therefore that maintenance costs be calculated at the design stage.

In some instances, it may not be possible to achieve BNG on-site – we are able to work across both rural and urban environments and tailor our approaches to biodiversity creation accordingly. Where BNG is not possible, we can work alongside developers to recommend alternative approaches – including the exploration of BNG via off-site units or through statutory credits.

Where off-site units are required, BNG provides opportunities for farmers and landowners to partner with developers to implement biodiversity enhancement measures on their land to at least the minimum 10% BNG requirements and they will receive a payment from the developer for doing so. At present, there are no guidelines for appropriate monetary values, and the sum(s) paid for taking land out of production and putting it forward for BNG development is to be negotiated on the open market. The terms of agreement between the farmers / landowners and developers is to be negotiated between the two parties, but is likely to be the minimum maintenance period of 30 years. BNG is also seen as a form of farm diversification and is therefore seen as an additional income stream related to land stewardship.

Statutory credits can be bought by developers as a last resort, when onsite and local offsite provision for habitat creation do not meet the BNG requirements. Biodiversity credits will be set higher than prices for equivalent biodiversity gain on the market. It is intended that this system will be run by a national body and not at a local level. The forthcoming DEFRA consultation on BNG secondary legislation will provide further clarification on this matter.

BoonBrown’s Landscape Architecture team seek to address BNG through creating spaces and places of benefit to nature through enhanced and better joined up habitats, where wildlife can thrive, through promoting health and well-being, through connecting people with the outdoors and creating more attractive and resilient places to work and live, natural capital assets also improve the economy and are a meaningful contribution towards climate change mitigation and net-zero targets.

For your BNG requirements, BoonBrown will be happy to work with you through this process, ensuring that your developments maximise their biodiversity value – leading to enhanced sites and more attractive and resilient places to work and live.

Designing Equitable Spaces

Blogs

Written by Abigail Baggley

Abigail is a qualified Architect and Architectural Director at BoonBrown with day-to-day responsibilities running our London Studio. She plays an important role shaping the company culture and is passionate about bringing holistic thinking to design with a focus on inclusivity and connectivity, finding opportunities for reuse and to recycle, and exploring ways to embed landscaping within design to maximise habitat creation.

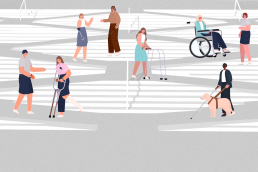

Understanding Equitable Design

Firstly, what is equitable design? The dictionary definition of equity, is to provide equal treatment to everyone whilst still acknowledging the differences between individuals. This implies that there are inherent differences between individuals’ circumstances, and for everyone to achieve the same equal outcome, they must be given tools and opportunities specific to their needs.

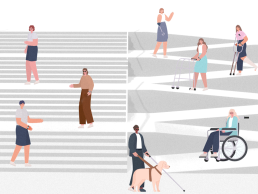

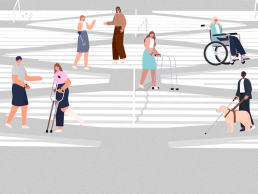

So how do these principles affect the design of urban spaces? To explore the concept, we felt it would be best represented as two graphics.

Scene one: from a practical perspective this succeeds in meeting the needs of its users, however, in this design there maybe experiential differences for those using the stairs vs those using the ramp. For example, how do the views beyond the space vary if you use the stairs or use the ramp, and are the lighting conditions different, and how do materiality choices change the feel of each space? There will be inherent differences between the users’ experience and therefore, we see an opportunity for more equitable design.

Scene two: in this option we explore another ramp and stair configuration delivering the same practical design outcome, however in this scenario it’s provided through a blended architectural design, where every user now has the same experience. People with all accessibility needs are catered for within one cohesive design, rather than segregated access arrangements where there will be inherent differences between what people experience.

We see equitable design as an opportunity to embed inclusivity within every design choice. This goes beyond equality and statutory requirement, and considers the detailed experience of each user, celebrating diversity and offering social experiences that are genuinely equal for everyone.

Diversity Matters

Blogs

Shanice Natalia

Shanice is a Level 7 Architect Apprentice, interested in writing about the mental health and well-being of young adults; championing inclusivity and community connections through food and architectural heritage; identity and immigration, specifically focusing on diaspora and establishing ‘Home’.

Could architects be doing more to address and provide solutions to the world’s current social, cultural and environmental issues?

As an industry, we generally try to be proactive and keep ourselves well informed and there is fundamental change happening within construction, along with a growing awareness in the wider society in relation to diversity and other commonly understood issues.

Diversity is often interchangeably used with ‘Inclusivity’, demonstrating the need for Intersectionality: whereby a range of demographics is acknowledged and recognised as having interdependent discriminative experiences, as defined by TOCA Architects.

Contrary to popular characterisation, diversity isn’t simply about race and forming a corporate level of cultural intelligence – it can be measured across the variables of age; sexual orientation; disability; gender; geography and ethnic background.

As society evolves and becomes more culturally aware, architectural practices are already keen in following suit, to present methods that mitigate biases within both the workplace and our projects – thinking beyond the ‘typical’ users of buildings and spaces.

Yet over the years, designing inclusively has not always been at the forefront of the design process which ultimately limited and, in some instances, continues to limit our ability to design effectively for all.

Within the architectural industry, diversity should not be a ‘nice to have’ but a moral obligation, and meeting more than the basic human needs of our communities.

The Architects Registration Board (ARB)’s 2020 survey corroborates the lack of representation of minority ethnic groups and women: 80% of architects classed their ethnicity as ‘white’ and only 29% of registered architects were women. Promoting inclusivity within the workplace is vital, as buildings are the products of today’s architects’ individuality. Thus, it is imperative that the industry successfully reflects the community for which it is ultimately designing.

New buildings should enhance the identity and inclusivity of neighbourhoods and should be able to adapt to everchanging community requirements; whereby public realm strategies strengthen community connections and promote our wellbeing. This is psychologically invaluable in bringing various aspects of the community together, whilst creating a legacy for future generations, who would be encouraged to improve their local environments.

Documents such as the National Space Standards and The London Plan, both updated annually, demonstrate the importance of inclusive and accessible affordable housing, whereby London’s growth and development is shaped by daily decisions made by planners; planning applicants, decision-makers; and Londoners across the city.

Organisations with a specific remit, such as ‘Future of London’ have discovered and advocated ways to design diversely, by starting at a smaller scale to focus on creating impactful design decisions to benefit the user. By designing for all, spaces and their users become more diversified and inclusive in their nature – thus emphasising that the architectural industry should be intrinsically diverse itself. Spaces are subconsciously assessed by their users, through the evaluation of how practical they are and whether it conforms to an inclusive environment, as opposed to imposing barriers of any kind.

One area where catering to the needs of a minority is most apparent, includes the work of the Royal National Institute of Blind People, who ensure that our streets are well planned for sight-impaired people to move around safely and comfortably, including the ways in which outdoor restaurants/cafés are situated on public pavements. Interestingly, by respecting these constraints, we are all able to benefit from tidier and better defined spaces, as there is an increased level of order.

Continuing with placemaking we also have the emergence of Innovation Districts nationwide, which seek to achieve long-term benefits and an overall positive contribution particularly to economically and socially deprived cities. Innovation Districts involve the combination of invention and enterprise to provide value-added growth through increased connectivity, stitching areas back into their surroundings and granting them a purpose beyond the ‘innovation’ community, as integral parts of the wider city. This is further demonstrated by ‘BeFirst’ who currently work to accelerate regeneration and promote diversity in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, through the parallel objectives of developing new homes and new jobs by 2037.

Diversity matters within public spaces and to produce safe and solution-oriented environments for users, involving a collaboration of several stakeholders to ensure the space has been effectively designed.

Everyone uses spaces differently and will have their own personal needs around buildings and public spaces. The feminist architectural practice ‘Equal Saree Architects’ in Spain have effectively developed ways in which cities can prioritise women’s needs in public places. Some factors considered include: the spatial arrangement of public toilets; reducing the domination of cars in Barcelona to provide more street space for pedestrians and cyclists to use the parks, benches, and playgrounds; alongside providing additional seating systems, as women tend to seek these for both mobility purposes and social interactions.

When designing public spaces, the following questions should be asked: What routes are taken to get from one place to another? Are there dark roads lined without natural surveyance – creating potential blind spots? Are there sites where large intimidating groups of people usually congregate? 71% of women in the UK have experienced sexual harassment in a public space (UN Women YouGov Survey and ONS 2021).

Extensive site mapping has revealed that girls and young women tend to be excluded from the design consideration of parks and public spaces. The organisation ‘Make Space for Girls’ has campaigned to specifically design spaces for girls and young women aged 16-24 in the UK.

Imogen Clark of ‘Make Space for Girls’ confirmed that spaces with water; nature; clear sightlines; sufficient lighting; and no dead-end footpaths, were classified as creating a ‘safe space’ for schoolgirls. Around London, Stratford’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park for instance, where there are many linear walkways, creates feelings of intimidation for young women by reason of groups of men reported to be gathering on this route.

A lack of consideration for female safety in public spaces creates feelings of isolation, fear, intimidation, and harassment. This is a consequence of poor lighting; a lack of non-linear footpath routes; which are typically found on highlines, canals and construction sites. BBC journalist, Stephanie Hegarty rightly stresses that “cities are supposed to be built for all of us, but they aren’t built by all of us.”

Critical principles that we should all be adhering to, to ensure that we practise diversely and produce inclusive designs within our projects:

- Acknowledging the true meaning of diversity, and the clear differences that our employees possess

- Offering choices where a single design solution cannot accommodate all

- Providing for flexible use, to anticipate future users’ changes in both the workplace and design projects

- Creating buildings and environments that are safe and enjoyable for all to use

It may be true to say that architects have not always designed as appropriately as they might have done, for a multitude of reasons or a possible lack of awareness that these issues even require solutions. However, at an early stage in my architectural career, I am fortunate to have found myself at BoonBrown who are conscious of these matters and take a proactive stance both within the workplace and on projects. I would hope and expect that other practices are equally cognisant of such considerations. It is important that we do not rest on our laurels and that we maintain consistent awareness of those around us in our ever-changing communities. We as architects, as those who influence and shape our society through buildings and spaces, have an obligation to respond to these constraints and recognise them as opportunities in our creativity, to design spaces that are beneficial for all.

Adaptive reuse; how old stories find new expression in North London

Blogs

Historical background

BoonBrown were approached by the City of London Corporation in 2019 to take on the renovation of 100 Brewery Road, located in one of Islington’s less salubrious corners. Previously used in the production of clothing, the existing mid-century, light industrial building was to be converted to 4700 m² of commercial space. The refurbishment included the creation of new access and circulation to the rear of the building, the creation of additional floor area through infilling of inset corners and a new third floor level of office space, with external terraces and newly introduced sustainable measures on the roof above.

Design approach

The design aspects of the project developed from two interrelated conceptual questions:

- On what reasonable basis can a building assume a new use?

- To what extent can it adapt to further functional changes?

These questions contribute to the enrichment of the current trend of adaptive reuse. This is an evolving concept and cannot be easily distinguished from the terms and practices of renovation or refurbishment, since each is aimed at improving the given conditions of an existing building and revitalising the structure, to ensure the preservation of the authentic character of the building, in accordance with a new use. However, the questions point to a certain difference; they imply our proactive attitude towards the nature of change. While strategically pursuing sustainable development in terms of both ecological and economic viability, the stance places a tactical focus on enriching values, more than identity, and emphasising performance more than mere existence.

Both ‘adoption’ and ‘adaptation’ positively embrace the given conditions as factors to be preserved and further interpreted to benefit from their inherent properties. By analysing and examining the original building, its use and subsequent disuse, the various attributes were considered and allowed to influence the vision of what it was to become. At the same time, the potential future use and type of tenants who might be attracted had to be acknowledged; bringing a modern aesthetic and such matters as sustainability and accessibility to the fore. Flexibility naturally played a role too, from both a commercial and user-fit perspective. Mediating between these supposed constraints and opportunities, the spatial, structural and material aspects were further examined and explored.

Spatial aspects

The existing building had become almost uninhabited and with declining value it was falling out of step with the surrounding urban context and the broader shifts in its economic paradigm. The project addressed spatial atrophy and renewal, seeking to accommodate diverse, lively activities, focusing on the task of configuring the newly expanded spaces. By taking the logic of the existing spaces into the new parts, to drive their contextual design response, it was then possible to implement a reciprocal reconfiguration of the existing spaces by adapting them to suit the new relationships. In this way we were able to establish a plausible link between the client and the users, in particular between what the landlord expected and what the tenants might expect, the latter therefore acting as the known variable.

And we sought to go further than simply considering how the spaces might be partitioned for flexible letting, but rather to imagine the production of accommodation that should be marketable over time, fundamentally creating a readily consumable spatiality.

The principle of production, guided by the upward arrangement of new uses, from warehouse distribution areas on the ground floor, to office above, thus shaped the vertical transition of the building’s character. It moved from an industrial hardware environment, to a robust yet comfortable, software supporting ambience. The transition was complemented by the horizontal relocation of the entrances for both pedestrians and vehicles, via perimeter circulation road, to the rear of the building. Simultaneously, the verticality and lateral relationship between old and new is celebrated by a full-height, front lit, atrium shaft which rising above the reception and spatially connects all floors. This also signals the new entrance externally, by virtue of the tall, strip of translucent material that introduces natural light deep within the added core. In effect, the compact core, offset to the rear, frees up the floorplates, to maximise not only the lettable areas but also the sense of space. This is most apparent at third floor level where the accommodation fluidly stretches out across the new terraces, offering panoramic views of the city laid out beyond.

Structural aspects

The building had remained static and unused for a significant period. Structural assessment undertaken by the engineers determined the need for a dual strategy; of reinforcement of the existing fabric, such that it could easily adapt to the new live and dead load demands, with integration of the infill parts and additional level, which imposed their own loads, while also providing a stabilising effect against lateral loading.

Given the original building lacked vertical bracing and previously relied on rigid connections for stiffness, the introduction of the infill parts provided a cost-effective solution to this part of the structural challenge. Importantly, this also further enhanced the future flexibility in terms of use and therefore the ongoing viability of the building.

Material aspects

With its identity, as well as value, decreasing over time, the building was left to deteriorate, unnoticed. Tackling the material depreciation of the building and reinvigorating it by the architectural response, its capacity for sensory stimulation has been reinstated, while the project came to unfold in the melding of various interior and exterior factors.

Internal treatment provides a rational core and Cat A office setting, allowing incoming tenants to fit out their spaces flexibly, yet with some gently derived definition. In the landlord parts, the project kept an industrial character with the new structural elements painted in matt orange, while the services are largely exposed in core areas and on office floors. The core stairs and secondary metal work are finished in black, offset against plain white walls, while polished concrete floors run through the core and metal access floors eagerly await tenant installations.

Externally, the internal aesthetic continues, with a modern industrial feel in the applied matt black aluminum cladding, used to envelop new parts. The existing pale yellow brick façade panels and the grid of concrete encased posts and beams which frame them, have been gently restored, while still articulating the urban context and building’s historic presence. Carefully inserted new window units meet today’s standards thermally and acoustically but also allow user control with opening for natural ventilation a retained possibility. The new top floor, largely set back from the lower façade, generates external amenity as terraces which provide physical relief to the building mass and sensory relief to the occupants. Above this sits external plant and a field of PV cells laid out in rows over a green roof background, providing the critical sustainable measures to be expected today.

The conceptual issues on adoption and adaptation were examined in spatial, structural and material aspects in order to capture a certain disparity between the existing and newly introduced conditions; to establish their balance and to facilitate their multilateral transition.

Our proactive attitude did not pursue a definitive answer, but rather the opportunity to determine the project’s potential.

Appropriately, the result is a commercial thread, stitched into the surrounding urban fabric and further woven into the patchwork of the London real estate market. The resultant product offers the immediate benefit of architectural, urban improvement and has gained a higher value, together with a refreshed identity of its own. However, the design strategies were developed and deployed to achieve long-term effectiveness, rather than immediate reward, though this is welcome too. The fundamental value of the project is as diverse as it is delicate and, somewhat paradoxically, is intended to surpass its currently designated identity. The subtle meaning can become more explicitly defined and potentially increasingly attractive over time, as the future customer-tenant relationship develops and the cycle of adaptive reuse goes on.